The Law of Triviality

“How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?”

Like most things coming out of the 17th Century, theology is firmly and perhaps obviously rooted in the question of angels dancing on the heads of pins. Way back when, Protestants coined this phrase to serve as metaphorical mockery of medieval scholars. Their mockery was pointed at theologians of the day who spent much time debating topics of no practical value or on questions whose answers held no intellectual consequence while more urgent concerns accumulated.

“Scornful description of a tedious concern with irrelevant details; an allusion to religious controversies in the Middle Ages. In fact, the medieval argument was over how many angels could stand on the point of a pin.”

— The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition. 2002

But if you take the Protestant mockery out of the equation for a second, this question philosophically underpins the more modern law of triviality. Cyril Northcote Parkinson, British historian and author, humorously coined this law in 1957. The law of triviality is distinctly critical of the business world, which I suppose is just a different kind of theology – the altar of capitalism, if one were to be so thoroughly cynical…

The “Bike Shed Effect”

Parkinson argued in his book “Parkinson’s Law” that the amount of time spent discussing an issue in an organization is inversely correlated to its actual importance. *chef’s kiss*

Anyway, this observation of corporate woes is more commonly known as the bike shed effect. The bike shed reference comes from the fictitious example Parkinson used to humorously illustrate this. Imagine, if you will, a company meeting agenda to discuss the budgeting of the following three items:

- A proposal for a £10 million nuclear power plant

- A proposal for a £350 bike shed

- A proposal for a £21 annual coffee budget

Perhaps we can first share a moment of silence for these hypothetical prices from 1957. But anyway, the team runs through the power plant proposal quickly. It’s too complex for anyone to really dig into, and most attendees have only general knowledge about the topic in the first place.

The discussion then moves to the bike shed. Everyone knows what a bike shed looks like and is comfortable weighing in with ideas on materials, design, and cost savings. They spend more time on the bike shed than the power plant.

When it comes to the coffee budget, everyone is an expert. They all have strong opinions about cost and value. By the end of the meeting, they’ve spent more time on the coffee budget than the shed and the power plant combined.

Parkinson’s original book is both hilarious and unnervingly relevant to those who have spent any time around bureaucracy. If you also fancy a chuckle, he weaves this brilliant tale from pages 64-72. Business and bureaucracy can serve as microcosms of broader international governance and cooperation. The tendencies that ail business are also the tendencies that ail us more broadly.

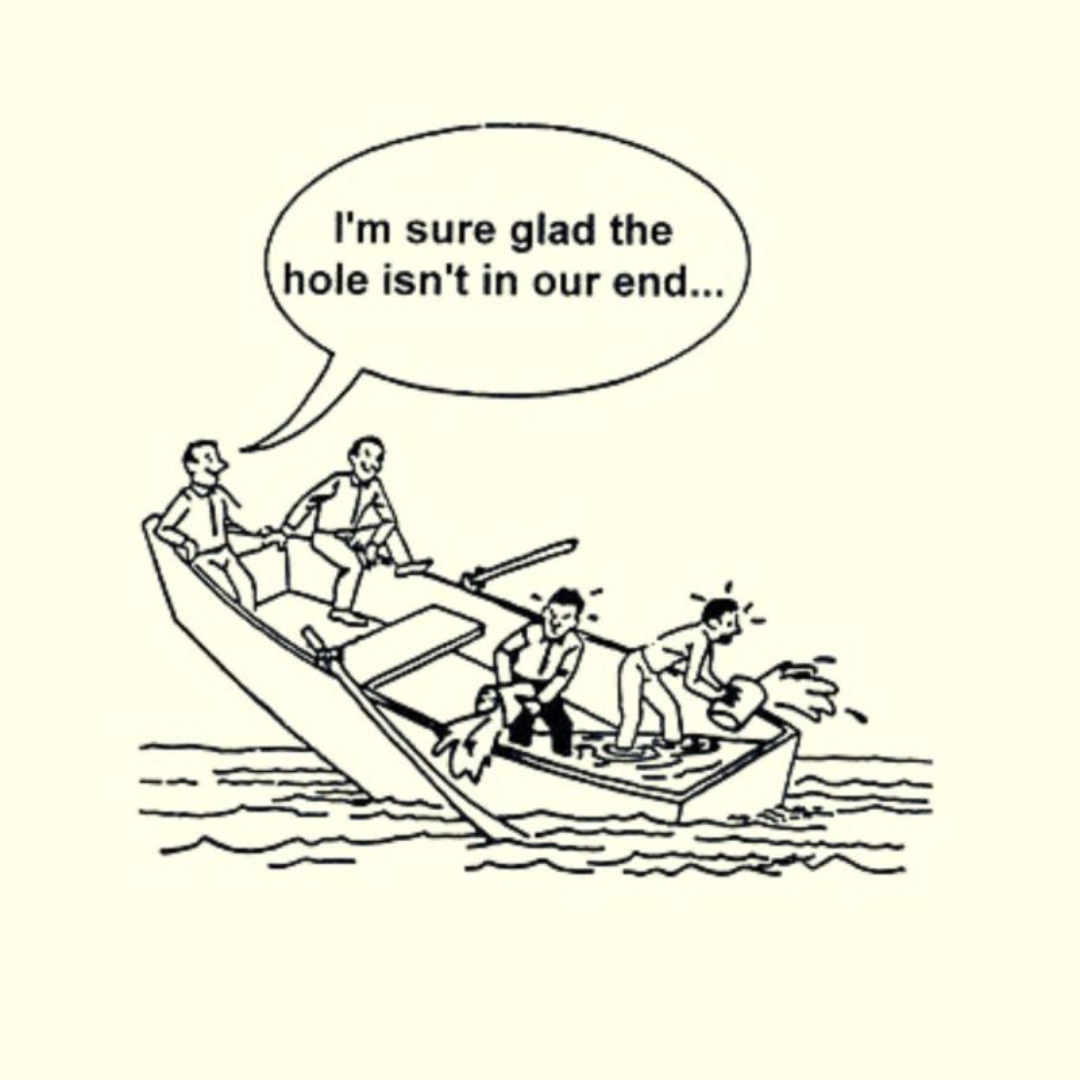

The bike shed effect is the tendency to spend excessive time on trivial matters, often glossing over important (and usually more difficult) ones. This brings us back to our original question about debating dancing angels. What questions are we asking (and spending precious time debating), both of ourselves and of our society more broadly?

What questions are we asking?

As Carl Sagan said, “We can judge our progress by the courage of our questions and the depth of our answers, our willingness to embrace what is true rather than what feels good.”

Here's an exceedingly relevant and modern-day example.

The United States just spent $5.5 billion dollars on the 2024 election. This money was spent by presidential candidates, political parties, and independent interest groups trying to influence federal elections. This doesn’t include the countless hours of airtime, the angry debates and rhetoric that flew through the social media sphere, and the mental energy expended by the population of a globalized world. And for what? For a political party to govern one country for the next four years. Four years. In four years, we’ll have to do this all over again.

So, we have the money. We have the passion and fervour. We have the mental energy to debate problems as global citizens. If nothing else, the 2024 US presidential election proved this in spades. Perhaps it’s time we point this invaluable trove of money, resources, and energy at something other than the next four myopic years. Perhaps we can start planting trees under whose shade we may never sit. Perhaps we can stop debating how many angels can dance on a pin and start asking questions whose answers hold intellectual consequence for generations of humanity to come.