An Economy of Gratitude

~7 min read

I am not an economist. My only experience is living in a capitalist country and, even then, Canada has a strong socialist culture. My observation is there are problems with unconstrained capitalism: left to themselves, the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. At some point the inequity becomes intolerable and the government has to step in to restrain unequal growth. Unless business is ready to build roads and hospitals, there will always be a role for government. In our current economic models, Earth, nature and natural resources are passive commodities to be used in the furtherance of the economy.

The relations between people are transactional. Without competition in the marketplace, there is no limit to the money companies can charge. What the market can bear is ok unless the product is essential. We have already seen grocery stores (there are only five major players - Walmart, Costco, Loblaw, Sobeys, and Metro) fix the price of bread to their advantage. Without food, people die. Should food be a commodity subject to market whims or should it be available for all at least at a minimum level? It gets cold out there. Should clothing be a commodity also subject to market whims or should everyone have access to clothing at some level?

"Braiding Sweetgrass"

Braiding Sweetgrass is a recent book by Robin Wall Kemmerer. Robin is Anishinaabemowin. She grew up living around Lake Michigan. Her writing and worldview are influenced by her Indigenous background. In her book she describes the gift economy. Giving and receiving gifts helps to bind the people together. Everyone likes to receive gifts and giving and getting gifts is part of the Anishinabek culture. (Getting and giving gifts is not just Indigenous, travel in the Orient often involves gift giving at the start of meetings…that’s where I got a lot of my ties.)

The gift economy has its own problems. With a gift, someone is indebted to someone, at least until the next gift is exchanged. This indebtedness helps to bind the community, but it also leaves people with an obligation.

The one thing that gift economy does bring to the table is the concept of the produce of Earth as gift. Traditional Indigenous communities had no concept of owning land. The land is not ours to buy and sell. It doesn’t belong to us. I struggled with this thought when we bought a parcel of land adjacent to ours. What right does anyone have to buy and sell land? Before we were here, there was land. Long after we are gone, there will be land. How does it come about that somewhere in-between somebody owns the land? Owning the land becomes part of the shared story we tell ourselves that defines our economy. But it is only a story and only means something to those who share the story.

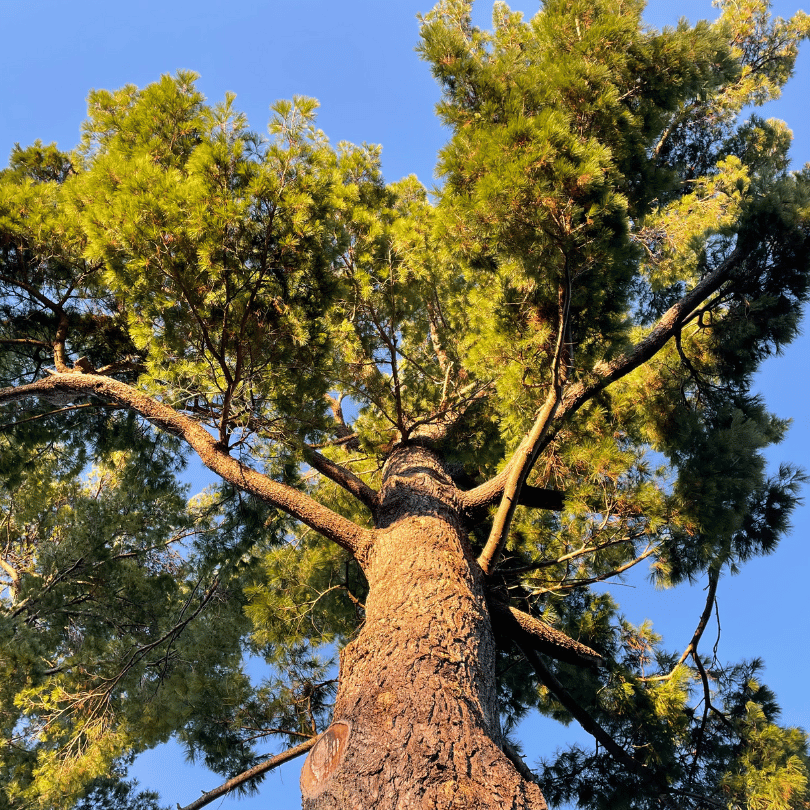

The land is a gift, the water is a gift, the trees are a gift, the sunlight is a gift. Gifts are part of our economy and we fail to acknowledge these gifts at our own peril.

Earth and Earth’s resources are not commodities, they are a gift from Mother Earth. We owe it to Mother Earth and to future generations to care for these gifts and to circulate them amongst all who live here, human and otherwise. In western culture, we inherit land from our parents. In Indigenous cultures, we borrow land from our children. It’s all about the worldview.

An Economy of Gratitude

Rather than striving for a gift economy that will be very difficult to administer, perhaps we should strive for an economy of gratitude. By acknowledging the things we receive as gifts, our worldview of want and excess becomes one of abundance and gratitude.

There’s a Raffi song about growing oats and beans and barley. The chorus is:

In a world of science and factory farms, the miracle of a new harvest is lost on us, and the struggle is reduced to productivity. If we can recover the sense of the miraculous in each harvest, then perhaps our gratitude will grow, and we can experience that gratitude.

In our household over the pandemic, we reduced our shopping to twice a month. Between shops we made-due with what we had and improvised as needed. At no time were we hungry. We just didn’t race down to the store every time we wanted something. Over the duration of the pandemic we accumulated twenty thousand dollars, money we didn’t spend. It’s still there and growing and we still shop twice a month. There is abundance if we chose to accept it. Rather than craving more stuff, we should embrace what we have and feel gratitude for what we have. There is a close link between gift and gratitude.

Frugal living is a growing topic these days. When I look at the recommendations for how to live frugally, mostly we are already doing this. Many if not most of my clothes have been repaired. Buying new clothes is an event. When clothes are thrown out, they are in dire condition. Making food stretch out and making clothes last are ways of walking lightly on the land and minimizing the impact on Earth. This becomes easier when a sense of gratitude is nurtured for each of the gifts we have.